Introduction to the geology of Myanmar

After decades of isolation, Myanmar’s opening in 2011 and initiated reforms raised hopes for democratization and economic development. Among methods to support Myanmar’s progress were scholarships, exchanges and research collaboration established with universities all around the world. Thanks to UNESCO/AGH Fellowships and NAWA (Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange) Myanmar students have also an opportunity to study at AGH University of Science and Technology, mainly pursuing degree in Economic Geology (3 MSc and PhD students in 2020/2021 and 7 in total). Access to good education for Burmese students through open and free academic exchange, once dream that have been become reality in the last decade, is important for the country development. Military coup in February and violent crackdown of mass protests struck at the heart of an aspirations of people across Myanmar. To draw attention and give some insight into this fascinating country, here’s a short overview of Myanmar geology.

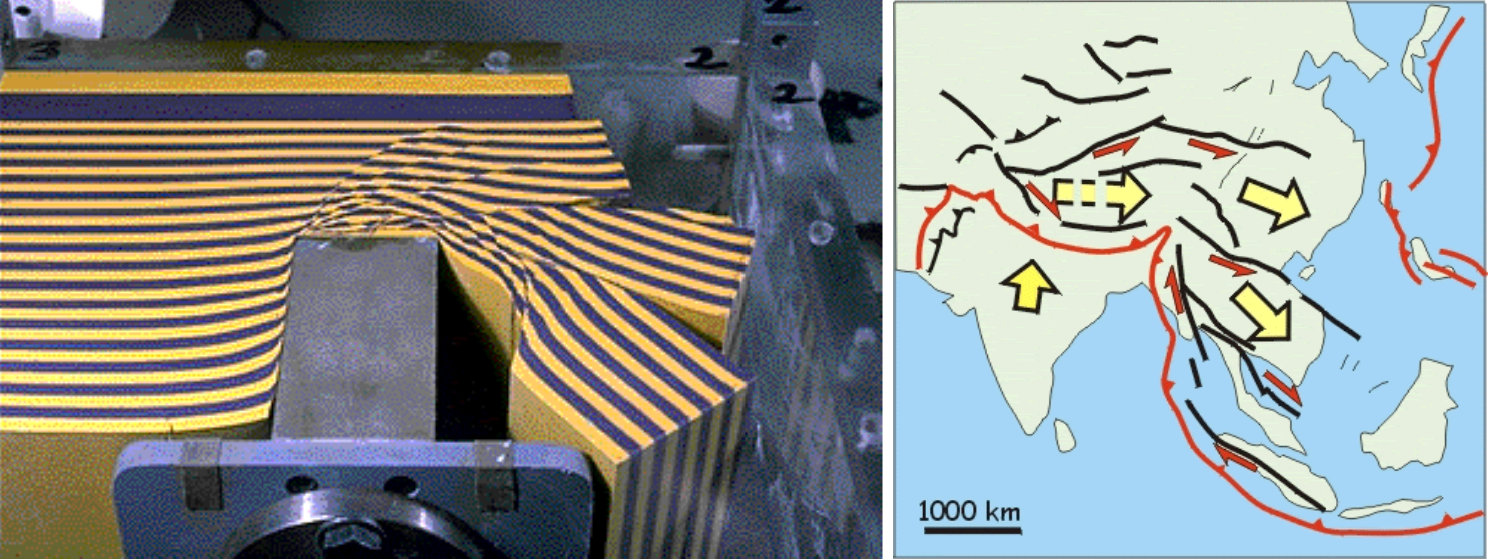

Let’s start with one of the most important and dramatic event in recent geological history (50 million years is fairly recent for many geologist). Geology of Myanmar and the rest of Southeast Asia is a product of long history including continental terranes separation from Gondwana, their northward migration, opening and closure of Paleo- and Neo-Thethys and final Gondwana rifting. 200 Ma India was a part of Gondwana, together with modern Africa, Australia, Antarctica, and South America, but in early Jurassic, when supercontinent started to break apart, India began slow drift to the north. Then, around 80 million years ago, the continent suddenly sped up. Present-day plates move at rates less than 10 cm/year, but plate reconstructions based on palaeomagnetic data suggest that for a period of 20 million years in the Cretaceous, the Indian plate moved at rate of 18-20 cm/year. Mantle plumes that broke up Gondwana might also melt and thin lower half of the Indian subcontinent, as Indian lithosphere extends only about 100 km deep, much lower than lithospheric roots in South Africa, Australia and Antarctica (180-300 km), additionally thickness of the Indian Plate could be further reduced as India moving north 65 Ma passed over the hotspots associated with the Deccan Traps (Kumar et al. 2007). Recently, additional model involving “double subduction” was also proposed (Jagoutz 2015). Suffice to say, India at high speed of 20 mm/year rammed into Asia and formed orogenic belt that created the Tibetan Plateau and the Himalaya Mountains. Most of the Asia was affected by this collision but keen observer can easily spot crucial detail. To the west rest of Eurasia and Alpide belt, formed by collison of Africa into Europe, stretch from Atlas Mountain up to Zagros, Hindu-Kush, Pamir Ranges and so on. Not much room left to move westward. To the east on the other hand, there are subduction zones along the entire coast of Asia and crust can be easily pushed in this direction. This process is called escape tectonics and was demonstrated by Tapponier in a famous plasticene experiment: rigid block is pushed into modelling clay and result has striking similarities to tectonic arrangement of present day South-east Asia (Tapponnier 1982).

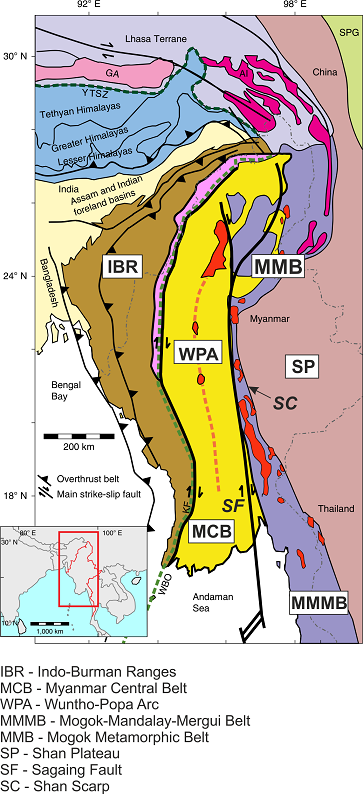

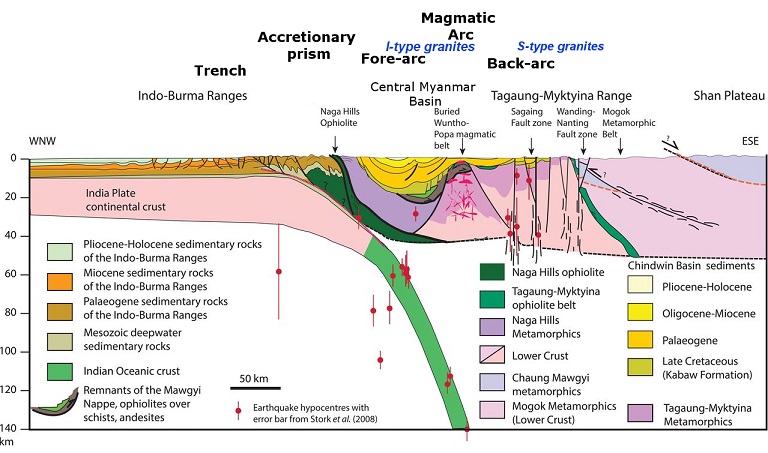

Myanmar lies at the junction of the Alpine–Himalayan Orogenic Belt and the Indonesian Island Arc System and has quite peculiar geography and geology. There are several parallel units (belts) all elongated/stretched in the N-S direction. Geology here can be roughly classified into four main tectonic units.

- From the West we start with the Indo-Burman Ranges, sitting at the convergent boundary of the Indian Plate and Burma microplate, west of the Indo-Burman Ranges lies the effective margin of Asian continent. The subduction formed accretionary wedges, later thrusted, folded and uplifted and as a result the Indo-Burman Ranges comprise flysch sediments and ophiolites.

- Second, there is the Myanmar Central Belt (a series of Cenozoic sub-basins considered as forearc/back arc basin) with the Wuntho-Popa Arc in the middle. It is a continental magmatic arc, N-S belt of Mesozoic to Neogene intrusive and volcanic rocks and Pliocene-Quaternary calc-alkaline stratovolcanoes (Mounts Popa, Taung Thonlon and Loimye).

- Third is kind of a Frankenstein-monster unit called the Mogok-Mandalay-Mergui Belt (MMM Belt) comprising the Mogok Metamorphic Belt, the adjacent Slate Belt (Mergui Group) and granites east of the Sagaing fault and west of the Paung Laung-Mawchi Zone.

The Mogok Metamorphic Belt is composed of metamorphic rocks: marbles, schists, gneisses of upper amphibolite, with locally granulite facies, intruded by a deformed granodiorite pluton and pegmatites. The Slate Belt is a late Palaeozoic succession of low-grade metasedimentary units (mudstones, wackes with occasional limestones). - Last but not least unit is the Shan Plateau, Cambrian-Ordovician sedimentary sequences unconformably overlain by thick Middle-Upper Permian limestone sequences. The Shan Plateau, with an average elevation of 1 kilometre, forms the eastern highlands of Myanmar and extends into Thailand.

To accommodate the India-Asia collision, extensive fault systems has developed with two major fault systems: Sagaing Fault and Shan Scarp. The strike slip Sagaing Fault is north-south, 1400 km long tectonic feature, and is remarkably linear in the central 700 km part. Northward, it terminates at the Jade Mine belt and splays into a 200 km wide compressive horsetail structure. Southward, it is connected to the active Andaman spreading rift. Shan Scarp, usually parallel and located east to the Sagaing Fault, is marked by the abrupt elevation change over a short distance (up to 1.8 km over few km) and show signs of reverse faults and largely overturned folds.

Figure from Searle et al. 2017 modified by additional description

Figure from Searle et al. 2017 modified by additional description

Eastern Myanmar, including the Shan Plateau, forms part of the Sibumasu (Sino- or Siam–Burma–Malaysia–Sumatra) Block, which extends from Yunnan in China through Myanmar to Thailand, the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra.

(A) Drilling at Kan Taung village, Mandalay Division; (B) & (C) Kwar Nyo Pin gold prospect, New Yon Village.

(A) Drilling at Kan Taung village, Mandalay Division; (B) & (C) Kwar Nyo Pin gold prospect, New Yon Village.

Myanmar is a country endowed with rich mineral resources including copper, gold, lead, zinc, silver, tin and tungsten ores According to USGS, in 2019 Myanmar with 14,2% share was the world’s third producer of tin and with 11,4 % share third producer of REO (Rare Earth concentrates). Let’s take a quick look at the most important ore districts.

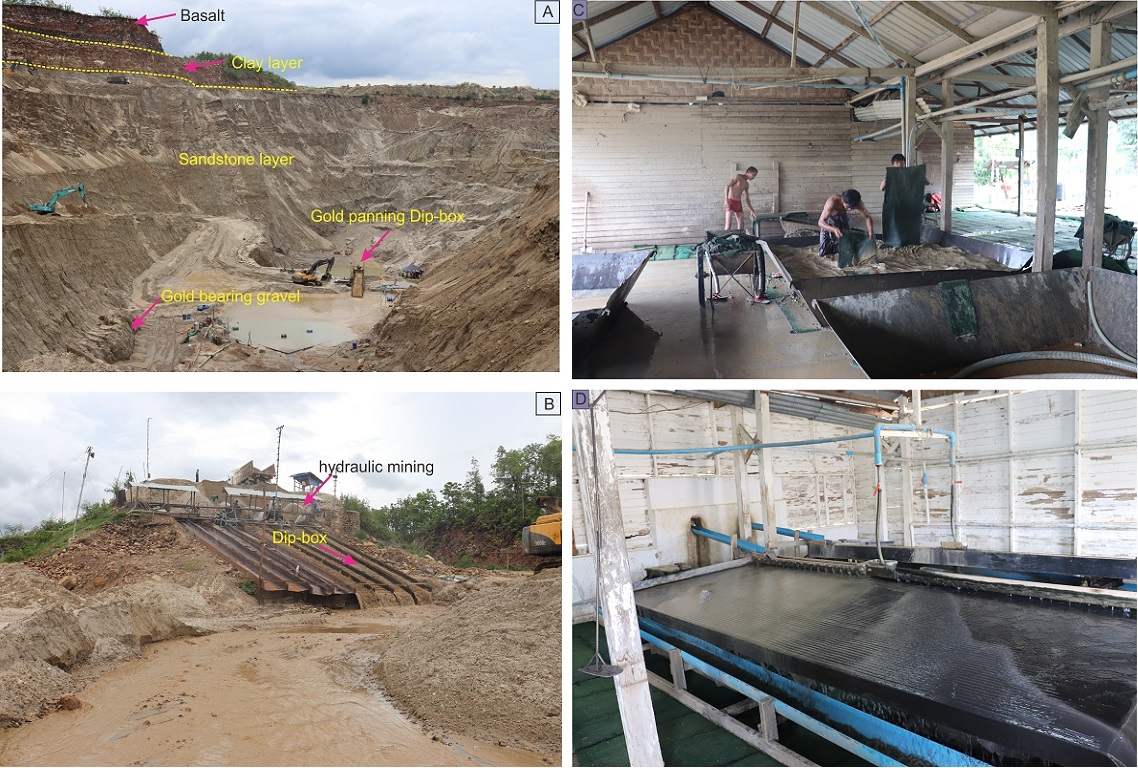

Open pit placer mining at Ye Myat Village

Open pit placer mining at Ye Myat Village

- Wuntho-Popa Arc host two main styles of mineralization: porphyry Cu and high-sulphidation epithermal polymetallic (Au-Cu) deposits with a world-class Monywa Cu copper district as prime example. It is a group of four high-sulphidation epithermal deposits exploited since 1980s with pre-mining combined resource of over 2 billion tonnes of Cu ore and over 7 million tonnes of Cu, making them a true giant.

- Granites of the Mogok-Mandalay-Mergui Belt, especially in Southern Myanmar, are known for their association with Sn–W mineralization. Typically, Sn–W mineralization occur in quartz veins or as cassiterite- and wolframite-rich pegmatites. Mawchi W–Sn mine located in Karen State was once one of the biggest producers of tungsten in the world, accounting for 10% of global production in the late 1930s. Tin is also mined from numerous placer deposits.

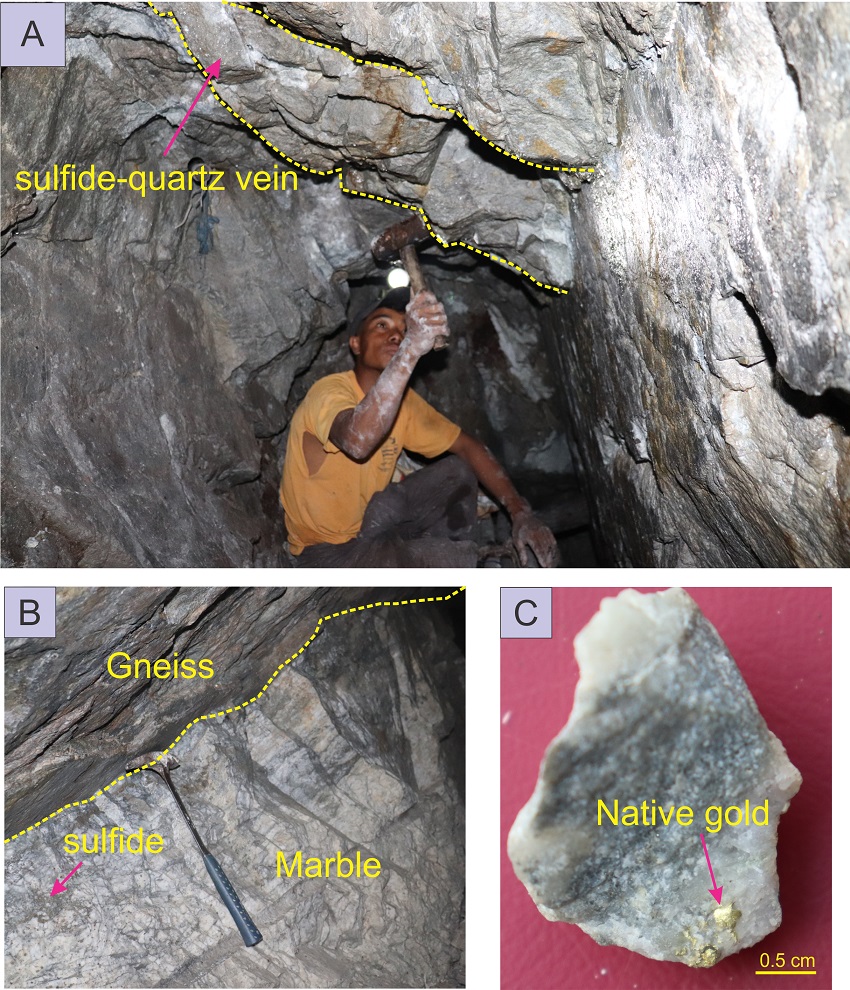

- Myanmar is sometimes called ‘the Golden Land’ due to abundance of gold-plated and gilded pagodas and stupas. Location of half-mythical “Suvarṇabhūmi” (meaning "Golden Land" or "Land of Gold" in Sanskrit) is still a matter of debate but some authors place it in the area of modern Myanmar. In 1756 King Alaungpaya of Myanmar sent a letter to King George II of Great Britain, engraved on a sheet of pure gold measuring 55 x 12 cm and decorated with 24 rubies. The Golden Letter is now preserved at the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Library in Hanover. Different styles of gold mineralization are found all around the country. Mineralization thought to be an orogenic gold deposits is present in the Slate Belt while native gold and base metal mineralization occur in veins and some of the skarns in the Mogok Metamorphic Belt. Sediment-hosted epithermal Au mineralization occur along the Sagaing fault zone with the largest gold-producing mine in Myanmar – Kyaukpahto Mine (premining geological resource estimate in 1996 of 6.4Mt at 3.0g/t Au). Mineralization occurs as stockwork hosted in the silicified sandstones of the Eocene Male Formation, and is associated with a system of extensional faults.

- Nickel and chromite mineralization occur in ophiolite fragments found within the country.

- Carbonate-hosted Pb-Zn sulphide deposits have been reported from the carbonate sequences of the Shan Plateau but by far the most famous and most important base metal deposit is the Bawdwin Mine. Before World War II this Pb-Zn-Cu VHMS deposit was one of the world's largest source of lead and silver. Interestingly, great contributions to develop this mine was made by Herbert Hoover: the soon-to-be 31st president of the United States but at the time just a mining engineer.

- Last but not least - gemstones. The World's finest rubies come from the area of Mogok, hosted by the metamorphic rocks of the Mogok Metamorphic Belt. Rubies, spinels, and sapphires, with a large number of other mineral species occur in marbles, adjacent to igneous intrusions, and in alluvial deposits. Myanmar is also famous for jadeitite from the Jade Mines Belt in Kachin State (source of the highest quality jadeite in the world) which may occur as outcrops in situ or as boulders in alluvial deposits. Another specialty of this region is burmite - “Burmese Amber” or “Kachin amber” found in the Hukawng Valley in northern Myanamar. It is of great palaeontological interest due to the diversity of flora and fauna contained as inclusions.

(A) local miner at Kwar Nyo Pin gold prospect, New Yon Village; (B, C) Kan Taung Village

(A) local miner at Kwar Nyo Pin gold prospect, New Yon Village; (B, C) Kan Taung Village

Myanmar is a highly prospective country but still relatively poorly explored and has great potential of hosting world-class ore deposits. A few big mining operations are active in the country but most of the production (especially in case of gold) come from the small scale local mining companies and artisanal mining.

Local gold mining at New Yon Village. Notice Thanaka (circular patch on woman cheek, C), paste made from pulverized tree bar traditionally used in Myanmar as sunblock and make-up.

Local gold mining at New Yon Village. Notice Thanaka (circular patch on woman cheek, C), paste made from pulverized tree bar traditionally used in Myanmar as sunblock and make-up.

Myanmar is endowed with a wealth of natural resources and has enormous potential to translate these assets into progress for its people. Unfortunately, over the years both army and rebel groups have directly or indirectly financed their activities and enriched their leaders through revenue generated from the control of resources such as jade, amber, timber. Conflict over the control of land and natural resources is particularly pressing in Myanmar’s resource-rich ethnic territories near the borders with China and Thailand.

Myanmar is home to the second largest total population of Asian elephants worldwide. Although the one from picture D lives in captivity, it is possible to encounter wild elephants during geological field works in remote areas. Picture E shows eggs of wild hens (ancestor of the domestic chicken).

Myanmar is home to the second largest total population of Asian elephants worldwide. Although the one from picture D lives in captivity, it is possible to encounter wild elephants during geological field works in remote areas. Picture E shows eggs of wild hens (ancestor of the domestic chicken).

To achieve long-lasting peace, questions who has rights over the country’s natural resources, and how the revenues from them can be shared more equitably with the local and wider population need to be solved.

Compiled by Krzysztof Foltyn; Proofreading and photos by Aung Myo Thu

Sources and reccomended literature:

Barber, A. J., Zaw, K., & Crow, M. J. (Eds.). (2017). Myanmar: geology, resources and tectonics. Geological Society of London.

Gardiner, N. J., et al. (2016). The tectonic and metallogenic framework of Myanmar: A Tethyan mineral system. Ore Geology Reviews 79, 26-45.

Gardiner, N. J., et al. (2015). Neo-Tethyan magmatism and metallogeny in Myanmar–An Andean analogue? Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 106, 197-215.

Mitchell, A. (2017). Geological belts, plate boundaries, and mineral deposits in Myanmar. Elsevier.

Source:

Source: